December has never been an easy sell in the music business. As the year winds down, attention shifts toward holidays, travel, and end-of-year lists, leaving little room for carefully planned album launches. For decades, labels treated the final month as a holding pattern, preferring to wait until January rather than risk a major release getting lost amid seasonal noise.

The 1970s, however, didn’t always follow industry logic. While December releases were fewer, some artists used the quiet window to their advantage, slipping bold statements into the market when expectations were low. In several cases, those records didn’t need aggressive promotion to find their audience—they grew through word of mouth, radio play, and the simple weight of the music itself.

Looking back, it’s striking how many enduring rock albums quietly arrived as the year was closing. These weren’t afterthoughts or leftovers from an overcrowded release calendar. They were fully realized works that went on to shape classic rock radio, influence generations of musicians, and redefine what a “December release” could mean. Here are five essential ’70s rock classics that proved the year didn’t need to end softly.

Hunky Dory by David Bowie (1971)

At the start of the 1970s, David Bowie was still searching for solid ground. His breakthrough hadn’t fully arrived, and there was a genuine moment when he considered stepping away from the spotlight to focus on writing songs for other performers. That uncertainty quietly shaped the early stages of Hunky Dory, which began as a loose collection of ideas rather than a grand statement.

Instead of sounding tentative, the album captures an artist sharpening his voice in real time. Bowie leaned into piano-led arrangements and character-driven songwriting, pulling influence from folk, pop, and theatrical storytelling. The record opens with an almost absurd run of inspiration, moving effortlessly from “Changes” to “Oh! You Pretty Things” to “Life on Mars?” without losing momentum.

What makes Hunky Dory endure is its balance of intimacy and ambition. These songs feel personal without being small, imaginative without drifting into excess. It marked the moment when Bowie stopped searching for direction and began defining one, setting the stage for everything that followed in his decade-defining run.

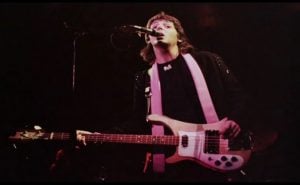

Band on the Run by Paul McCartney and Wings (1973)

The early years after The Beatles were not kind to Paul McCartney in the press. Critics questioned his artistic direction, and Wings was often dismissed as a lightweight project. Just as work on Band on the Run was about to begin, the situation worsened when key band members unexpectedly walked away.

Left with a stripped-down lineup, McCartney responded by tightening his focus. Recording largely as a trio, he leaned into melody, structure, and sheer musical confidence. The album unfolds like a mini-epic, shifting moods and textures while maintaining a clear sense of forward motion.

Rather than playing it safe, Band on the Run sounds fearless. Songs like “Jet,” the title track, and “Nineteen Hundred and Eighty-Five” are dynamic without being cluttered, ambitious without losing clarity. Released in December, the album quietly rebuilt McCartney’s reputation and remains one of the strongest statements of his post-Beatles career.

Hotel California by Eagles (1976)

By the mid-1970s, the Eagles had evolved far beyond their country-rock origins. Each album pushed them closer to a sleeker, harder-edged sound, and Hotel California represented the full arrival of that transformation. The addition of Joe Walsh added bite and unpredictability to an already formidable guitar lineup.

At the same time, the band’s songwriting sharpened. Themes of excess, disillusionment, and the darker side of success run throughout the album, giving it a cohesion that rewards start-to-finish listening. The production is polished, but never sterile, allowing the music to breathe even at its most dramatic.

Released late in the year, Hotel California didn’t feel like a seasonal afterthought. From the haunting pull of the title track to the reflective close of “The Last Resort,” the album captured a specific cultural moment while remaining timeless in its execution.

Running on Empty by Jackson Browne (1977)

Jackson Browne had built his reputation on deeply personal songwriting, but Running on Empty found him presenting those stories in a new context. Instead of recording in a traditional studio, Browne captured much of the album on the road, using hotel rooms, backstage spaces, and live venues.

That approach gave the record an immediacy that perfectly suited its themes. Songs like the title track, “Shaky Town,” and “The Load-Out” feel more lived-in when recorded between shows. The performances carry a looseness that never sacrifices precision or emotional weight.

What sets Running on Empty apart is how naturally it blends introspection with momentum. It’s an album that sounds like movement itself, making its December release feel especially fitting—arriving as one year ended and another was about to begin.

London Calling by The Clash (1979)

In the UK, London Calling landed just before Christmas, a bold and unexpected release for a band rooted in punk’s raw minimalism. Instead of doubling down on aggression alone, The Clash expanded their sound dramatically, delivering a sprawling double album that refused to sit still.

The record pulls from reggae, rockabilly, ska, soul, and straight-ahead rock without sounding scattered. Tracks like the title song and “The Guns of Brixton” sit comfortably beside more personal moments such as “Lost in the Supermarket” and “Train in Vain.”

London Calling works because its ambition never outweighs its conviction. Whether addressing political unrest or everyday alienation, the album hits with clarity and urgency. It closed out the decade not with nostalgia, but with a forward-looking statement that still resonates.